Venezuelan-born revolutionary who led the wars of independence against Spanish rule and became the central symbolic figure of Latin American sovereignty and unity.

Liberated multiple South American territories from Spanish rule, envisioned a unified Latin American republic, and became a lasting symbol of sovereignty, authority, and national destiny.

- 1783-07-24 — Born

Born in Caracas into a wealthy Creole aristocratic family under Spanish colonial rule. - 1810 — Revolutionary Commitment

Commits fully to the independence movement following events in Caracas and Europe. - 1813 — Admirable Campaign

Leads successful military campaign liberating western Venezuela. - 1819 — Gran Colombia Founded

Establishes the Republic of Gran Colombia, uniting modern Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama. - 1824 — Final Military Victory

Patriot forces secure decisive victory over Spanish rule in South America. - 1830-12-17 — Death

Dies in exile and political isolation in Santa Marta.

No results found.

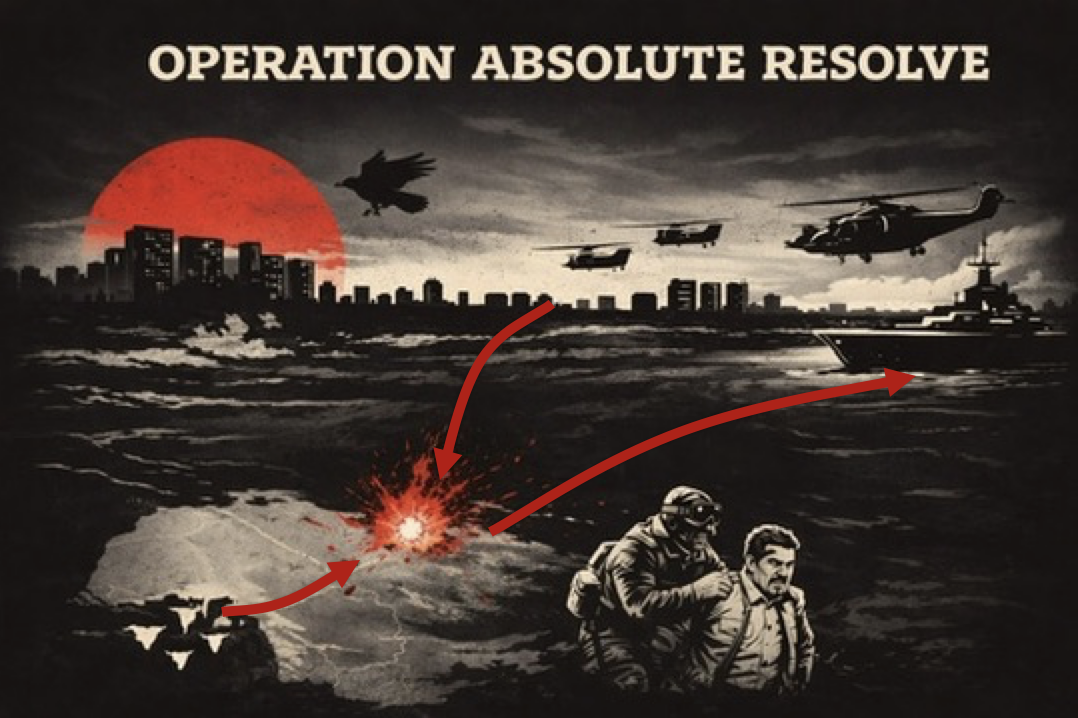

Chávez-Maduro Period in Venezuela

From 1999 to early 2026, Venezuela moved from an oil-rich state with functioning institutions

into a prolonged national breakdown defined by collapsing services, mass emigration, and

governance sustained increasingly through coercion and external leverage. The period closes

with the U.S. capture and detention of Nicolás Maduro on 3 January 2026.

U.S. arrests Nicolás Maduro

Simón Bolívar emerged from the contradictions of colonial society. Born into privilege yet shaped by loss, European education, and Enlightenment thought, he developed a fierce rejection of imperial domination. His early exposure to revolutionary ideas in Europe combined with a deep awareness of Spanish American fragmentation and elite rivalry.

Bolívar’s revolutionary career was defined by persistence rather than linear success. Military defeat, exile, and internal betrayal were constant. Yet he adapted, learned, and returned. His authority rested less on ideology than on personal legitimacy forged through sacrifice, endurance, and command under extreme conditions.

Unlike later national leaders, Bolívar did not primarily seek office. He sought order. His central concern was not liberation alone but post-liberation stability. He feared that newly independent societies would collapse into factionalism, demagoguery, or foreign domination. This fear shaped his preference for strong executive authority and limited mass democracy.

Bolívar’s vision of Gran Colombia reflected both ambition and anxiety. He believed that only unity could protect the region from renewed imperial control. Yet regional interests, elite resistance, and personal rivalries undermined the project. Bolívar increasingly ruled through decree, convinced that republican virtue was insufficient without discipline.

By the end of his life, Bolívar was politically isolated. The states he helped create fractured. His dream of continental unity failed. Yet this failure did not erase his symbolic power. Bolívar became larger in memory than in life-a figure endlessly reinterpreted by successors seeking legitimacy.

Bolívar’s legacy is therefore foundational but unstable. He is not a coherent doctrine but a reservoir of authority. His name has been used to justify liberal reform, military rule, socialism, and populism alike. What endures is not his constitutional design but his role as a legitimizing ancestor for power in Latin America.