What a Nation Remembers in the Morning.

“What does a nation remember when it rises in the morning?”

– A question that lingers across the Baltic Sea, where memory and future cross like currents between shores.

Crossing Waters

In the autumn of 2013, I crossed the Gulf of Finland. Ninety kilometers from Helsinki to Tallinn, aboard a ferry filled with quiet commuters. Among them, Estonian workers on their weekly rhythm: five days building in Finland, two days back home. Some reading a newspaper. Others talking – a beer in hand. Some stared out over the dark water. Their voices carried not complaint, but the weary cadence of purpose. Work, family, return. Their movement wasn’t migration in the classic sense — it was economic necessity in free circulation. Still, something felt lopsided: a weight was shifting from one shore to the other.

That weight is part of the Baltic’s burden.

On the ferry, I met a man who told me something I later asked others to confirm. During Soviet times, Estonian families would tune their antennas to Helsinki and watch Finnish television. The news, the Western shows — it was their glimpse into another world. The Soviets knew. They couldn’t trace your clicks or search history back then. But they had other ways. In school, children were sometimes asked to draw what they’d seen on television. If they sketched Finnish anchors or foreign images, it was a quiet signal. The house was watching the wrong sky.

The Long Shadow of Empire

Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania. These countries on the northeastern edge of the European Union form more than a regional cluster — they are a passage, a boundary, a historic compression zone. For centuries, they were run over, divided, absorbed: by Sweden, Prussia, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and most enduringly, by the Russian Empire.

Lithuania, once the Grand Duchy and proud half of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, retains a complicated pride. It was once the second-largest state in Europe, with influence extending far into modern Ukraine and Belarus. But that legacy came at a cost: conquest, partition, and the burden of having been both victim and empire.

Estonia and Latvia have Hanseatic roots — seafaring, trade-driven, German-influenced. But they too were swept up by Tsarist and later Soviet tides. Today, they carry the memory of forced collectivization, deportations, and a generation that still speaks Russian by default — not always by choice.

These entangled legacies linger in language, policy, and posture.

The Burden of Memory

Vilnius was once known as the Jerusalem of the North. Its Jewish population shaped the intellectual and spiritual life of Eastern European Jewry. But the Holocaust struck early and hard here. In his book In Europa, Dutch writer Geert Mak recounts how local collaboration in the early extermination of Jews preceded even Nazi occupation in some areas. Whether out of ideology, fear, or long-suppressed grievance, the violence was swift and devastating. This dark fact, too, is part of the Baltic burden.

And the minorities that remained — Russians, Poles, Belarusians — did not always feel welcome in the new nations that emerged after 1991. Some language policies, though rooted in legitimate national restoration, began to exclude. In Estonia, large Russian-speaking communities found themselves outside the full circle of civic inclusion. In Ukraine, similar dynamics fed resentment in Donbas. The principle of “one state, one language” clashes with a multilingual reality born of empire.

It is a delicate balance: affirming national identity without erasing lived diversity.

| Background Insight: |

|---|

| For a deeper comparison of language laws across Europe — from South Tyrol to Samtskhe-Javakheti — see our Background article Return to Babel: Language, Borders, and Belonging. It traces how states use language as a tool of nation-building, sometimes at the cost of pluralism. The Baltic case is not unique. |

The Migration Dilemma

The Baltic states have lost people — by war, by exile, and now, by aspiration.

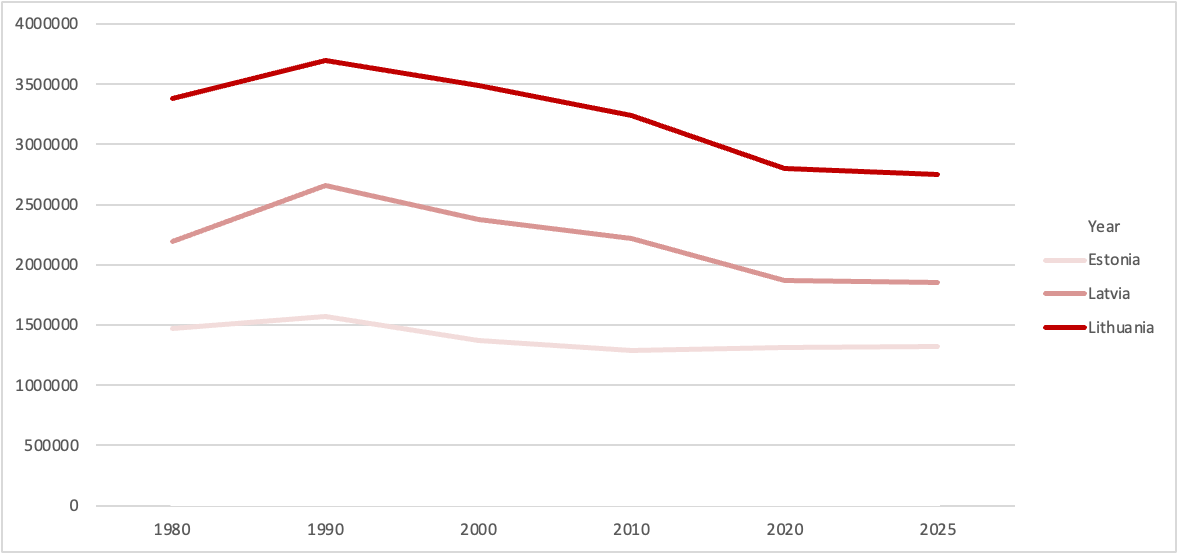

Source from World Bank, UNDESA, Eurostat

Since the 1990s, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania have all experienced population decline. Lithuania alone dropped from 3.7 million to around 2.8 million between 1990 and 2020. Much of this is due to emigration: young professionals, skilled workers, entire families seeking better wages in Germany, the UK, or Finland.

And yet, this movement has not been replaced. Refugees from Ukraine have been accepted, but broader immigration — from Syria, Afghanistan, or Africa — meets resistance. Demographic anxiety mixes with cultural conservatism. “We want our people back,” is a common refrain. But economies move faster than sentiment.

The result is a generation gap — and an emotional one.

Strategic Position, Fragile Ground

Geographically, the Baltics are a hinge: between Scandinavia and Central Europe, between Poland and the Russian sphere. Their ports — Tallinn, Riga, Klaipėda — are coveted logistical points. Their rail lines, energy grids, and digital networks are crucial to NATO and the EU. But they are also vulnerable.

Russia’s aggression in Ukraine has reignited fears. The Suwałki Gap, a 100-km corridor between Poland and Lithuania, remains a strategic pressure point. And in some Russian-speaking districts, particularly in Estonia, the risk of psychological subversion is real. If language laws isolate, and if loyalty is questioned, some may be seduced by false narratives of “liberation.”

This, too, is part of the burden — not of guilt, but of responsibility.

A Bridge, Not a Buffer, A Call for Action

The Baltic states must not be treated as a buffer zone. Nor as fragile peripheries to be coddled. Their burden is also their potential: to be a strategic bridge. In cybersecurity, Estonia leads. In civic innovation, all three countries are laboratories. Their cultural history, from Jewish Vilnius to Hanseatic Riga, deserves recognition, not simplification.

Europe must not only defend the Baltics — it must invest in them. In infrastructure, in population return programs, in nuanced minority policy. And in a narrative that shows: these lands are not the edge. They are part of the center.