How identity is filtered — not by law, but by design – and what it means to belong

“If they are one people with one language, nothing will be impossible for them… So the Lord confused their speech and scattered them over the face of the earth.”

— Genesis 11 (paraphrased)

The Tower of Babel is usually told as a warning: about pride, confusion, collapse. But it also echoes something older. In the creation command, humanity was told to go forth, multiply, and fill the earth. The scattering of languages wasn’t the end of culture. It was its beginning.

What followed Babel wasn’t destruction — it was pluralism.

Different tongues. Different places. Different ways of being human.

Europe protects languages — on paper

And yet today, across Europe and far beyond, we find ourselves attempting to reverse that story. To fold back plurality into singularity. To make language serve power, not identity. To treat diversity as danger — and uniformity as strength.

What happens when we try to force a return to Babel? And who benefits when we do?

Europe protects languages. It says so in law. In charter preambles and constitutional clauses, in multilingual websites and minority councils, the message is clear: cultural diversity is not just allowed — it is part of what Europe is.

But legal text doesn’t always translate into reality. And exclusion rarely announces itself as law — more often, it comes through procedures, requirements, and silence. The right to speak one’s language does not guarantee the right to be understood — by the court, the school, the job examiner, the tax office. The result is a continent where pluralism is promised, but unevenly practiced.

This isn’t authoritarianism. It’s state logic. And it follows a familiar pattern.

The Post-Occupation Reflex

Across Eastern Europe, language policy has often followed the same sequence: occupation → independence → reaction. When a state has been ruled by another power, the first act of reclamation is usually linguistic. This was true after the Soviet collapse. But it was also true after the Austro-Hungarian breakup, after the expulsion of Germans following World War II, and even earlier.

Language, in these moments, becomes more than speech. It becomes boundary. Identity. Control.

This explains — but does not excuse — much of what happened after 1989. In Estonia and Latvia, large Russian-speaking populations were left behind when the USSR disintegrated. To build national identity, the new states required proficiency in the state language for citizenship, government work, or access to education. It was a sovereign response. But it also left tens of thousands stateless.

In Ukraine, efforts to strengthen the role of Ukrainian in public institutions culminated in the 2019 language law. It made Ukrainian mandatory in most official contexts — even in regions where the population spoke Russian or Hungarian.

Again — not repression. But not real inclusion either.

Other countries chose more covert paths. Romania, under Ceaușescu, didn’t ban Hungarian outright. It simply reshaped demographics, moved populations, and ensured that Hungarian-speaking communities would be outnumbered — and therefore institutionally sidelined. A smarter move than others — and more dangerous in its subtlety. No bans required. Just math.

Elsewhere, post-war Hungary and Czechoslovakia treated German-speaking minorities with harsher tools. Expulsions, removals, erasures. The mechanisms vary — but the pattern holds:

After domination ends, identity hardens. Language becomes territory.

When Protection Isn’t Access

The gap between legal protection and functional participation runs through most of Europe.

You may have the right to speak your language — but if no interpreter is provided, no school is funded, no court recognizes the document, then the right is decorative. In Slovakia, Hungary, and Bulgaria, Roma communities are told their culture is protected — while their children are shunted into special schools, or left with teachers who don’t speak Romani at all.

In Latvia, a Russian-speaking grandparent may pass the language test and gain citizenship. But if they don’t, they remain a non-citizen — legal but voiceless. In parts of Ukraine, Russian or Hungarian speakers can go to school — but find that their diplomas, exams, and career paths depend entirely on Ukrainian proficiency. Again, no ban. But real consequence.

This is not discrimination by decree. It is filtering by design.

Russia’s Accusation — and the Mirror It Offers

Russia claims to protect Russian speakers in the near abroad. It uses this claim to justify pressure, intervention, even war. And while the motives are hollow, the critique touches something real.

In the Baltics and Ukraine, policies have often made life harder for Russian speakers — not to punish them, but to sever the lingering threads of empire. That effort is understandable. But it becomes dangerous when it makes individuals carry the weight of history.

At the same time, Russia’s internal record is no cleaner. It recognizes dozens of minority languages — Tatar, Bashkir, Chuvash — but allows almost none of them to flourish. In 2018, Russia made minority language study optional. Instruction hours dropped. Russian remains the unchallenged default in administration, higher education, media, and law.

So the Kremlin’s accusation is a mirror: Europe sees only the propaganda, and misses the reflection. Because while Europe may not repress language, it often allows exclusion to settle quietly. The mechanisms are different. But the outcomes rhyme.

Language has become a tool for sorting, for filtering, for deciding who belongs — and who doesn’t.

When It Works

There are places where this story looks different.

In Belgium, for all its complexity, handles language with constitutional serious. Dutch-, French-, and German-speaking communities are formally recognized. Schools, courts, administrations are built around this pluralism. There are frictions. But no one questions the citizenship of the other. French-speaking Belgians do not want to be French. Dutch-speaking Belgians do not identify with the Netherlands. Their languages do not imply different nations — only different voices.

South Tyrol is another working model. Finland protects Swedish and Sámi — not just as cultural ornaments, but as languages with institutional standing. Even Georgia, while asserting its national language, has built local structures for Armenian and Azeri education — and while Russian remains widely spoken, particularly among older generations, it holds no formal status — though a ban seems out of question.

These aren’t perfect systems. But they show that linguistic pluralism can be constitutional, lived, and stable.

Consequences

When states make access to society conditional on language — especially when that language once represented the occupier — it is often the most vulnerable who lose: The elderly who cannot pass integration tests. The children who grow up speaking one tongue at home and another at school — but feel at home in neither. The stateless. The sidelined. The quietly filtered out.

You don’t need to criminalize a language to erase it. You just need to make it irrelevant to power. And once power speaks only one tongue, everyone else learns to whisper — or to stop speaking entirely. It just needs to be rendered inconvenient. That’s enough to disappear it from public life.

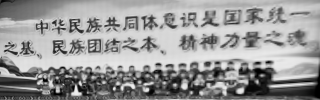

Sidenote – towers are everywhere

This is not only a European question. In the United States, Spanish is not banned — but it is socially ranked.

In China, the state celebrates its 56 ethnic minorities with murals and cartoon smiles — but only Mandarin is promoted, taught, funded, and legally dominant. Cultural diversity is framed — but linguistic uniformity is enforced. From Texas to Xinjiang, from Paris to Lviv, language remains a tool of control as much as a medium of culture.

Conclusion: The Tower We Build

This isn’t just about speech. It’s about access. About dignity. About whether Europe is willing to live up to what it claims — that identity can be plural, and memory can coexist.

This was never about rewriting laws. It’s about how language is used — not to ban, but to sort. To filter. To reward. To quietly close doors. The difference between speaking and being heard is the difference between permission and belonging. And Europe, if it still believes in values, must choose the latter.

Babel was not the end of civilization. It was the beginning of cultures.

To suppress language — or to privilege one above all others — is not progress.

It is a return. A return to Babel. Not to scatter, but to centralize. Not to liberate, but to build a tower. A tower not for God, but for the autocrat. Stone by stone. Tongue by tongue.

The question is not which language dominates. The question is: what kind of world are we building, when only one is allowed to speak?

References

- Council of Europe (1992). European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

- OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities (2020). Report on Statelessness in Latvia and https://index.statelessness.eu/country/latvia

- Venice Commission (2017). Opinion on the Law on Supporting the Functioning of the Ukrainian Language as the State Language

- Amnesty International (2022). Roma Children in Segregated Schools: Slovakia and Hungary

- Brill – Linguistic Rights and Education in the Republics of the Russian Federation: Towards Unity through Uniformity

- Council of Europe (2021). Minority and Regional Languages in France: Constitutional Challenges

- Minority Rights Group (2023). Music Beyond Borders: Language, Culture, and Resistance in Turkey

- PBS (2025). Talking Black in America – Social Justice

Appendix A: Comparative Language Law Table

| Country | Minority Language Policy | Russian Language Status | Public Use (Courts, Admin, Signage) | Education Language Law | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estonia | Recognized (but restricted use) | Not official; ~25% speak it | Allowed in private; limited official use | Gradual transition to Estonian-only schools (by 2030) | Non-citizenship issue for many ethnic Russians |

| Latvia | Recognized, limited rights | Not official; ~30% speak it | Russian banned in public administration since 2022 | Russian schools phased out after 2024 reforms | Referendums rejected Russian co-official status |

| Lithuania | Recognized | Recognized but minimal presence | Limited use in local government where >60% | Minority language schools allowed | Less confrontational policy |

| Ukraine | Formerly official regionally (pre-2014) | Now excluded as minority language | Banned from courts and education since 2019 | Ukrainian-only law in public education | Criticized by Venice Commission |

| Hungary | Strong protections (esp. Hungarian abroad) | N/A | Full rights for minorities where present | Minority schools fully legal | Opposes Ukrainian language law for Hungarians |

| Romania | Minority languages allowed | N/A | Allowed locally where >20% population | Hungarian, Romani schools exist | Hungary often protests treatment of Székely |

| Slovakia | Official Slovak only | N/A | Use allowed >20% threshold | Slovak mandatory; minority schools exist | Tightened restrictions post-2009 |

| Poland | Recognized | Minority but not regionally concentrated | Limited to cultural institutions | Polish-only schooling, minor bilingual education | Historically assimilative |

| Finland | Swedish is co-official | Recognized immigrant language | Finnish and Swedish both mandatory | Bilingual schooling protected | Russian community small, integrated |

| Belgium | Dutch, French, German = official | Russian not recognized | Depends on region (Flemish/Walloon) | Multilingual schooling per region | Highly institutionalized federalism |

| Switzerland | 4 official languages (DE, FR, IT, Romansh) | Russian not recognized | Local autonomy | Schooling depends on canton | Model of linguistic coexistence |

| France | French-only policy (Jacobin model) | Not recognized | No minority languages in administration | French-only in public schools | Corsican, Breton excluded |

| Germany | Recognized: Sorbian, Danish etc. | Russian as immigrant language | Regional use permitted | Schooling mainly in German; exceptions exist | Integration over autonomy |

| Austria | Minority protections exist | Not officially recognized | Recognized where minorities live | Croatian, Slovene schools exist in Carinthia | Stable, limited minorities |

| Spain | Co-official in regions (Catalan, Basque, Galician) | Russian not recognized | Full autonomy in some regions | Immersion in regional languages legal | Regionalism = deep linguistic rights |

| Italy | Recognized (Ladin, Slovene, German) | Russian not recognized | Use allowed in designated zones | Some bilingual schooling | Historical minorities only |

| Czechia | Limited recognition | Not official | Czech only for most purposes | Minority schools exist, rare | Russian declining post-2022 |

| Serbia | Recognized (Hungarian, Romani, etc.) | Russian not recognized | Local use permitted | Schools exist in Hungarian, Slovak, others | Diverse linguistic base |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina | Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian co-official | Russian not present | Local use defined by canton/entity | Schools use local language depending on region | Post-war decentralization |

Key Observations:

- Baltic States (especially Latvia and Estonia) have strictest Russian language restrictions in the EU.

- Ukraine shifted from multilingual tolerance to strong Ukrainian-only policies post-2014 and especially 2019.

- France remains unique in total exclusion of minority languages from public life.

- Spain, Switzerland, and Belgium represent models of multilingual governance—though not without political strain.

- Russian narratives exaggerate discrimination, but partial truth exists, especially where Soviet settlers were never fully integrated.

Appendix B: Selected Films on Language, Identity & Exclusion

These selected documentaries explore how language connects — and divides — across societies, institutions, and memory.

Talking Black in America – Social Justice (PBS, 2025)

A powerful documentary that explores how African American Vernacular English affects educational access, legal fairness, and workplace opportunities—demonstrating that dialects, not just languages, can shape belonging and exclusion.

Music Beyond Borders (Minority Rights Group, 2023)

A compelling short film on Kurdish communities in Turkey, exposing how language policies can marginalize culturally recognized groups—often under the guise of national unity.

Speak Freely: Bilingual Lives in Belgium (2022)

An intimate portrait of families navigating the Dutch‑French linguistic divide in Brussels, showing how institutional multilingualism functions—and occasionally, how it fractures communities.

Voices Under Pressure: Tatar Education in Russia (2020)

A sobering account of post‑2018 language reform in Tatarstan, where removal of mandatory instruction in Tatar schools triggered debate over cultural assimilation, identity, and local autonomy.